三毛登上纽约时报:撒哈拉、爱情与死亡(双语全文)

2018年起,《纽约时报》推出了“被遗漏的逝者”(Overlooked)栏目,开始补发历史上该报因“性别歧视”而遗漏的(已故)女性讣告。该栏目讲述了一些伟大女性的故事,纪念她们给社会留下了难以磨灭的印记。

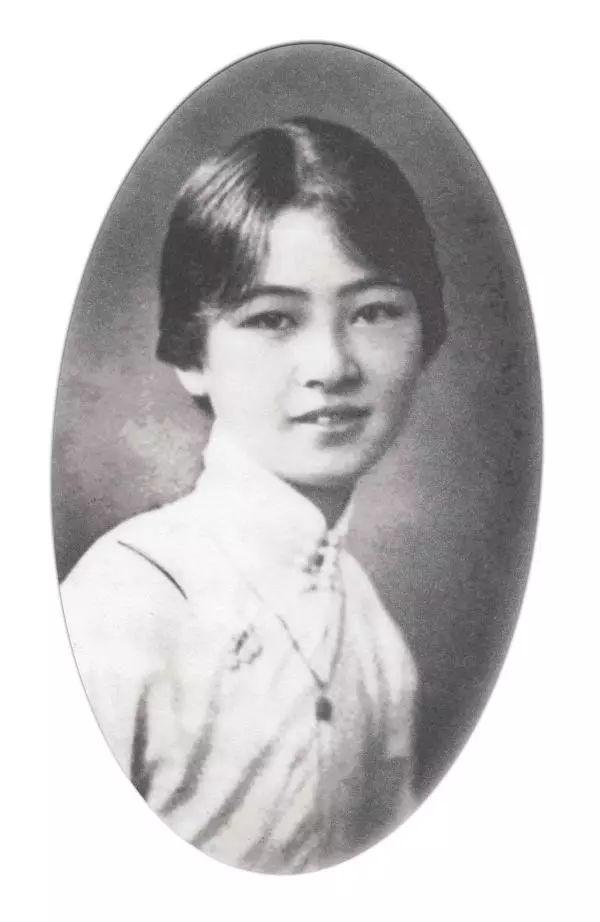

登上这份报纸的中国女性一共有三名:一名是中国女权和女学思想的倡导者,为推翻满清政权和封建统治而牺牲的革命先驱秋瑾。

另一名是中国著名建筑家和作家林徽因。

点击图片,查看林徽因讣告

还有一名就是中国近现代作家——三毛。文章详细地介绍了三毛的生平以及创作。

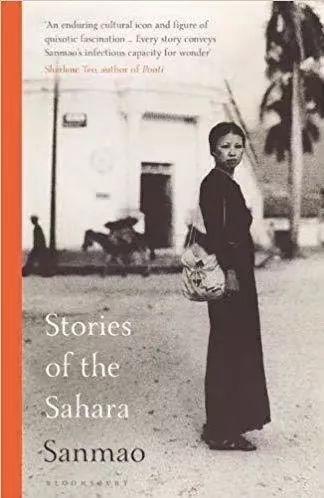

除此之外,《撒哈拉的故事》英文版即将于本月在英国出版,明年1月美国出版,这也是三毛作品第一次有英译版问世。

Sanmao, ‘Wandering Writer’ Who Found Her Voice in the Desert

“流浪作家”三毛:撒哈拉、爱情和死亡

In the early 1970s, the Chinese writer Sanmao saw an article about the Sahara Desert in National Geographic magazine and told her friends that she wanted to travel there and cross it.

20世纪70年代初,台湾作家三毛在《国家地理》杂志上看到一篇关于撒哈拉沙漠的文章,随后告诉朋友她想去那里旅行,并穿越撒哈拉沙漠。

They assumed she was joking, but she would eventually go on that journey and write that the vast Sahara was her “dream lover.”

朋友们以为她在开玩笑,没想到她最终踏上旅程,并撰文称,广袤的撒哈拉沙漠是她的“梦中情人”。

“I looked around at the boundless sand across which the wind wailed, the sky high above, the landscape majestic and calm,” she wrote in a seminal 1976 essay collection, “Stories of the Sahara,” of arriving for the first time at a windswept airport in the Western Saharan city of El Aaiún.

她在发表于1976年的经典散文集《撒哈拉的故事》中写道,当她第一次来到撒哈拉,到达撒哈拉西部阿尤恩市一座狂风肆虐的机场时,“我举目望去,无际的黄沙上有寂寞的大风呜咽的吹过,天,是高的,地是沉厚雄壮而安静的。”

“It was dusk,” she continued. “The setting sun stained the desert the red of fresh blood, a sorrowful beauty. The temperature felt like early winter. I’d expected a scorching sun, but instead found a swathe of poetic desolation.”

“正是黄昏,”她继续写道。“落日将沙漠染成鲜血的红色,凄美恐怖。近乎初冬的气候,在原本期待着炎热烈日的心情下,大地化转为一片诗意的苍凉。”

1990年的三毛,拍摄者肖全

It was one of many adventures she would have, and the books of essays and poetry she went on to write would endure among generations of young women in Taiwan and China who viewed her self-assured prose and intrepid excursions as glorious transgressions of local conservative social norms.

这是她将要经历的诸多冒险之一,她此后写下的散文和诗歌在台湾和中国的几代年轻女性中流传,她的文字中流露出的自信和深入当地探索的勇气,被她们视为是对当地保守的社会规范的勇敢挑战。

Sanmao died in 1991 after publishing more than a dozen books of essays and poetry, but she has not been forgotten. An account that publishes lines from her books on Weibo, a Twitter-like Chinese social media platform, has more than a million followers.

在发表了十多本散文集和诗集后,三毛于1991年去世,但人们并没有忘记她。在中国类似Twitter的社交媒体平台微博上有一个账号专门摘选她作品里的一些文字,现在该账号有100多万粉丝。

And a new English translation of “Stories of the Sahara” will be published by Bloomsbury in the United Kingdom next month and in the United States in January. Mike Fu, the book’s translator, said it would be the first English translation of any of Sanmao’s books.

下月,布卢姆斯伯里(Bloomsbury)出版社将在英国推出《撒哈拉的故事》一书的英译版,并于明年1月在美国推出。该书翻译傅麦说,这是三毛所有作品的第一部英译本。

“The fact that she’s been able to endure this long in the Chinese literary imagination is something else,” said Fu, the assistant dean for global initiatives at the Parsons School of Design in New York.

“她能在中国文学创作中如此长盛不衰,实在非同一般,”纽约帕森斯设计学院负责全球项目的副院长傅麦说。

One reason may be that her writing style resonates with a current generation that is accustomed to self-promotion and oversharing on Twitter and Instagram.

其中一个原因可能是,她的写作风格与习惯在Twitter和Instagram上自我推销和过度分享的这一代人产生了共鸣。

“Although ubiquitous in the contemporary age of social media and commercialized feminism, Sanmao’s unabashed self-aggrandizement and position of gung-ho empowerment was ahead of its time,” Sharlene Teo, a Singaporean novelist who lives in Britain, wrote in the introduction of the English edition of “Stories of the Sahara.”

“尽管在社交媒体和商业化女权主义的当代,毫不掩饰的自我张扬和积极赋权已经无处不在,但三毛的精神领先于她的时代,”现居英国的新加坡小说家张温宁在英文版《撒哈拉的故事》的序言中写道。

At the same time, Teo wrote, her soaring self-confidence is frequently undercut by descriptions of her isolation, melancholy and “world weariness.”

然而,张温宁又说,她对自己的孤独、忧郁和“厌世”的描绘,常常会折损她那飞扬的自信形象。

The essays, which were originally published contemporaneously in a Taiwanese newspaper, paint a portrait of the native Sahrawis, a nomadic people who have lived in the desert for generations. The Sahrawis fought a decades-long armed resistance against the countries — Spain until the mid-1970s and then Morocco that administered the Western Sahara, a territory that stretches from Algeria and Mauritania in the east to the Atlantic coast in the west.

这些散文最初是在当时的一家台湾报纸上发表的,描绘了世代生活在沙漠中的游牧民族沙哈拉威人的生活。他们与西班牙和摩洛哥展开了数十年的武装抗争。对西班牙的抵抗一直持续到20世纪70年代中期,接着是摩洛哥。后者当时统治西撒哈拉,也就是东起阿尔及利亚和毛里塔尼亚、西至大西洋海岸的一片区域。

Sanmao became immersed in Sahrawi communities, and sometimes trained a critical eye on some of their customs. She reacted in horror, for example, to a traditional wedding ceremony in which the goal was to take a young bride’s virginity violently.

三毛逐渐融入沙哈拉威人的生活,有时对他们的某些习俗投以批判的眼光。比如,她对婚礼上粗暴夺走年轻新娘的童贞的传统感到憎恶。

“That the ceremony had to conclude in such a way was deplorable and ridiculous,” she wrote in an essay called “Child Bride.” “I got up and strode out without saying goodbye to anyone.”

她在一篇名为《娃娃新娘》的文章中写道:“我对婚礼这样的结束觉得失望而可笑,我站起来没有向任何人告别就大步走出去。”

Other essays document Sanmao’s life as a bohemian expatriate. On her wedding day, for example, she treats her outfit as an afterthought as she throws on sandals and a hemp dress and pins a sprig of cilantro to her hat. Then she and her fiancée walk for nearly 40 minutes through the desert to a courthouse for the ceremony.

还有些文章记录了三毛的波西米亚式侨民生活。比如,结婚那天,她对自己的穿着没有太放在心上,穿了一条麻布裙,脚蹬一双凉鞋,帽子上别一把香菜,就和未婚夫在沙漠里步行近40分钟去法院结婚了。

“I didn’t own a purse,” she wrote, “so I had nothing to hold.”

她写道:“没有用皮包,两手空空的。”

Her prose, which oscillates between memoir and fiction, has a laconic elegance that echoes the Beat poets. It can also be breezy, a remarkable quality at a time when her homeland, Taiwan, was under martial law in an era known as the “White Terror,” in which many opponents of the government were imprisoned or executed.

她的散文介于回忆录和小说之间,有一种让人想起垮掉一代诗歌的简洁优雅。同时它们又是轻松愉快的,与她的故乡台湾当时所处的“白色恐怖”戒严时期相比,这是一种不寻常的品质。那时许多反政府人士正被监禁或处决。

“She established a different and exotic place, a castle in the sand, for readers to enjoy,” said Carole Ho, a professor of literature at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. “At a time when materialistic enjoyments were pretty limited in Taiwan, she yearned for something different, and showed younger girls that it’s O.K. to be unique.”

“她建起了一个与众不同、充满异域风情的地方,一座供读者欣赏的沙中城堡。”香港中文大学文学教授何杏枫说:“在台湾那个物质享受极为有限的年代,她渴望不一样的东西,并向比她年轻的女孩证明,独一无二是可以接受的。”

Sanmao, who wrote under a pen name and sometimes went by Echo Chan, was born Chen Ping on March 26, 1943, during World War II, into a well-educated Christian family in Chongqing, a city in southwest China. Her father, Chen Siqing, was a lawyer, and her mother, Miao Jinlan, was a homemaker.

1943年3月26日,三毛出生于中国西南城市重庆一个知书达礼的基督教家庭。她的父亲陈嗣庆是律师,母亲缪进兰是家庭主妇。

After the war, the family moved east to Nanjing, and shortly fled to Taiwan in 1949.

战后,三毛一家搬到东部的南京,在1949年逃到台湾。学生时代的三毛很不安分,她花了大量时间阅读中国和西方的文学作品,包括《飘》和《基督山伯爵》。

Sanmao was a restless student who spent much of her time reading Chinese and Western literature, including “Gone With The Wind” and “The Count of Monte Cristo.”

学生时代的三毛很不安分,她花了大量时间阅读中国和西方的文学作品,包括《飘》和《基督山伯爵》。

One day in school, she wrote an essay about wanting to be a garbage collector so that she could roam the streets and find discarded treasures. When her teacher called the idea nonsense and made her start again, she doubled down — by writing that she wanted to be a Popsicle vendor.

有一天,她在作文中写到她想成为一个捡垃圾的人,这样就可以在街上闲逛,发现被别人丢弃的宝贝。老师说她简直一派胡言,要她重新再写,结果她变本加厉,写她想当一个卖冰棒的小贩。

After studying philosophy at Taiwan’s Chinese Culture University, Sanmao moved to Spain in 1967, later studied in Germany and worked briefly in the law library of the University of Illinois.

在台湾中国文化大学修完哲学专业之后,三毛于1967年移居西班牙,此后在德国深造,并在伊利诺伊大学法律图书馆短暂工作了一段时间。

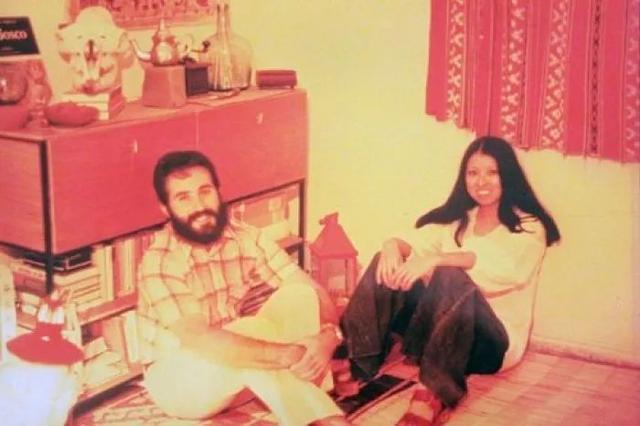

She met her future husband, José María Quero, when she was 24 and he was 16 and they lived in the same neighborhood.

24岁时,她遇到了未来的丈夫荷西·马利安·葛罗,当时,荷西16岁,他们住在同一个街区。

“She had studied philosophy, languages, literature,” Carmen Quero, José’s sister, told the Spanish newspaper El País in 2016 about meeting her. “We were fascinated by her. He fell in love with her at first sight.”

“她学习过哲学、语言和文学,”2016年,荷西的姐姐卡门·葛罗在接受西班牙报纸《国家报》采访时,谈到与她见面的经历,“我们都被她迷住了。他对她一见钟情。”

They married in 1974 and settled in Spain’s Canary Islands, where Sanmao wrote the lyrics to “The Olive Tree,” a song popularized by the Taiwanese singer Chyi Yu:

他们于1974年结婚,在西班牙加那利群岛定居。在那里,三毛写下了后来风靡一时的歌曲《橄榄树》的歌词,这首歌的演唱者是台湾歌手齐豫。

Do not ask me where I’m from

My hometown is far away

Why do I wander around

Wandering afar, wandering

不要问我从哪里来

我的故乡在远方

为什么流浪

流浪远方,流浪

In 1979, the year the song was released, María Quero, a scuba diver and underwater engineer, died in a diving accident. Sanmao returned heartbroken to Taiwan in 1981.

1979年,也就是这首歌发行那年,身为潜水员和水下工程师的荷西在一次潜水事故中丧生。三毛悲伤欲绝,1981年回到台湾。

“She gave love and passion to everyone, but José took away an important part of her,” Lucy Hsueh, a Taiwanese painter and one of her closest friends, said in a phone interview.

三毛的好友、台湾画家薛幼春在接受电话采访时说,“她给予每个人爱和激情,但荷西带走了她生命中重要的一部分。”

Sanmao spent part of the next decade teaching creative writing, becoming affectionately known as the “wandering writer.” Among other places, she traveled in Central and South America on a six-month travel writing assignment from United Daily News, the Taiwanese newspaper that had published her essays from the Sahara.

在接下来的10年里,三毛教授创意写作,被人们亲切地称为“流浪作家”。她游历了很多地方,其中包括为了完成台湾《联合报》约稿,在中美洲和南美洲旅行了6个月。该报曾刊登过她在撒哈拉沙漠时的文章。

Sanmao returned to her birthplace on the Chinese mainland in April 1989. The trip inspired her to write the screenplay for “Red Dust,” a 1990 film about a love story set in Japanese-occupied Shanghai.

1989年4月,三毛回到她在中国大陆的出生地。这次旅行启发她写下了后来名为《滚滚红尘》的电影剧本。这部电影于1990年上映,讲述了上海日占时期的一个爱情故事。

Sanmao died in a Taiwanese hospital on Jan. 4, 1991. She was 47. The death was ruled a suicide and prompted an outpouring of grief in Taiwan.

1991年1月4日,三毛在台湾一家医院去世,终年47岁。她的逝世被判定为自杀,并在台湾引发巨大的悲痛。

Some speculated that her heartbreak over losing her husband had been too much to bear.

有些人猜测她是因丈夫去世太过悲痛而自杀的。

“Her extra 12 years after José passed away were for her parents,” said Hsueh. “Perhaps she left us to attend a reunion she had long promised to attend.”

“荷西去世后的12年里,她只是为父母活着,”薛幼春说。“也许她离开我们是为了去和她早已答应的人团聚。”

Sanmao had once written of doing just that. “Jose, you promised to wait for me on the other side,” she wrote in “The Immortal Bird,” a 1981 essay about her own mortality. “As long as I have your word, I have something to look forward to.”

三毛曾经写过要这样做。“荷西,你答应过的,你要在那边等我,”她在1981年谈论死亡的文章《不死鸟》中写道。“有你这一句承诺,我便还有一个盼望了。”

Crown, Sanmao’s longtime publisher, released her collected works in 2010. More recently, the Canary Islands and the Western Sahara have become popular destinations for Chinese tourists. Some Chinese websites offer directions to the Saharan church where Sanmao was married, and to a nearby hotel called the San Mao Sahara.

长期与三毛合作的皇冠出版社于2010年出版了她的作品集。近些年,加纳利群岛和西撒哈拉成为中国游客的热门目的地。有些中国网站还提供去三毛在西撒哈拉结婚时的教堂和附近一家名为三毛撒哈拉旅馆的路线。

One of her last books, “My Treasures,” is a collection of 86 short essays that celebrate clothing, jewelry, hand-decorated bowls and other objects that she had purchased during her travels.

三毛最后的一本书《我的宝贝》收集了86篇短文,描述了她在旅行期间购买的服装、珠宝、手工装饰的碗等物品。

In one essay, Sanmao pauses to analyze her own wardrobe, and lands on a metaphor.

在其中一篇文章中,她停下来对自己的衣橱作了一番分析,然后写了一个隐喻。“

“The jeans I was wearing were bought in Shilin, my boots were from Spain, my bag was from Costa Rica, and my jacket was from Paris,” she writes. “An international smorgasbord; and you could say they all united harmoniously and peacefully — and that’s exactly me.”

下面的牛仔裤买自士林,长筒靴来处是西班牙,那个大皮包——哥斯达黎加,那件大外套,巴黎的,”她写道。“一场世界大拼盘,也可以说,它们交织得那么和谐又安然,这就是那个我吧。”

- THE END -

往 期 精 选

「点击图片 查看文章」

陈奕迅朗读的《小王子》太好听了!超地道的英音!(中英双语+视频)

漫威电影为什么不算电影?斯科赛特的解释让人伤感(双语全文)

文拓视野 译悦心灵

长按•识别二维码•加关注

一个专业、开放、有趣的翻译平台

点击下方“阅读原文”,购买《英语世界》更多英语学习资料

评论